Opioid use is changing our communities. These highly addictive drugs claim the lives of two Albertans a day and disrupt community life at all levels. This special feature looks at how southern Alberta is responding.

Our coverage of opioid drug use in Alberta is a partnership with Alberta Health Services and its Apple magazine. The following stories and photos give our readers a glimpse into the lives of people whose lives are affected by the crisis, including the people who are living with addiction and the people who are helping them and their communities.

Story by Lisa Kozleski

Photos by Rob Olson

Five years ago, city editor Nick Kuhl says, the Lethbridge Herald only occasionally ran stories about opioids and addiction. Today, they appear weekly.

Ten years ago, Wood’s Homes supervisor Shauna Cohen says, it was rare to learn of the death of one of the young people who she and her colleagues knew or who accessed Wood’s Homes’ services. Over the past several years, that’s something they’ve had to face – more than once.

Fifteen years ago, Lethbridge Correctional Facility deputy director Shane Hoiland says, inmates told him they would have done just about anything to get cocaine. Today, they tell him they WILL do anything to get opioid-based drugs.

For those living with addiction, the opioid and meth crisis that has engulfed this province has changed everything. For their family and friends, it has created deep wounds and heartbreak. But beyond that, the crisis has also changed the very nature of how people – including Kuhl, Cohen, Hoiland and scores of others – do their work. Lethbridge College graduates working in the fields of policing, corrections, child and youth care, nursing, journalism, emergency response and beyond have had to quickly acquire new skills, expand and adapt procedures, and seek solutions to problems that didn’t even exist when they started in their careers.

"I’ve never seen anything grow this fast in my 15 years of policing. We’ve never seen anything like it.”

They’ve seen the change come quickly and broadly across their community. It’s affecting how they’re protecting their community’s safety and ensuring the wellness of others. And it’s changing how they care for people in their professions.

“When they say we have a crisis,” says Lethbridge Police Service’s Sgt. Christy Woods, “people underestimate how it’s grown. It’s grown like technology has grown. Exponentially. I’ve never seen anything grow this fast in my 15 years of policing. We’ve never seen anything like it.”

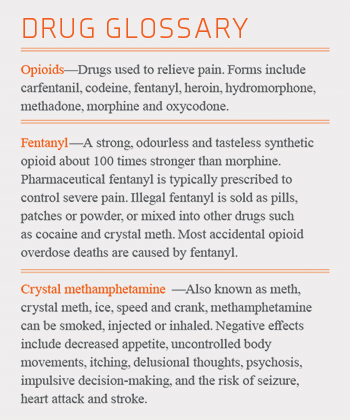

Part one: Looking back

Woods (Conservation Enforcement 1999) spent four years at the beginning of her career with the Lethbridge Police Service in the downtown beat unit. There, she saw the first growth and transition from alcohol to cocaine addictions on the street. In 2017, after working for several years as a detective, she returned to the patrol division. The streets had changed. Now, she says, “fentanyl use is commonplace, and many of the clients I knew as alcohol addicts years ago had now become fentanyl users. From overdoses to sudden deaths, the effects of this drug were readily apparent.”

In the last year, Woods explains, the crisis was made worse by the increase across the city in the use of methamphetamine, or meth. “It’s mixed in everything now,” Woods says, creating a more devastating outcome as meth, a stimulant, is incredibly addictive and causes paranoia and violent, unpredictable behaviours, while fentanyl, a depressant, can cause overdoses and death.

Jennifer Ross (Nursing Education in Southwestern Alberta 2005), an emergency mental health nurse at Chinook Regional Hospital in Lethbridge, and others working in health services share similar memories of the arrival of opioids and meth in southern Alberta. They say the introduction of the drugs was quick and deadly.

“I first started to notice the crisis a couple of years ago, when the drugs began to change in Lethbridge and the surrounding areas. Typically we would see individuals using cocaine, crack, marijuana and alcohol,” says Ross. “I remember seeing my first [fentanyl] ‘bean.’ I had no idea what it was and no idea how deadly it was. I felt like one day it wasn’t there and the next it was all you heard about. Since then, it’s a repeated and daily issue that I see in my job and in my community.”

Meth’s arrival also seemed to happen overnight. Ross explains it was like “BAM, meth was here and here hard. The meth use was becoming more of an issue for us as it was hard to determine when someone was psychotic because of drugs or a [mental] illness. Either way, we still needed to treat the symptoms and keep people safe.”

For Chelsey De Groot (Child and Youth Care 2010; General Studies 2012; Bachelor of Applied Arts – Justice Studies 2015), the arrival of the crisis was marked by an increase in the number of people dealing with addiction as well as a decrease – in attendance at programming, that is. De Groot is the cultural program coordinator with ARCHES, a not-for-profit, community outreach group in Lethbridge, and in the past year she has noticed a sharp drop in the number of participants in the cultural programming she organizes for at-risk people called I’taamohkanoohsin (Everyone Comes Together).

“We had started setting up a tipi in Galt Gardens every other Friday and the program grew from there,” De Groot says. “I have always worked with vulnerable populations experiencing homelessness, mental health and addiction issues. Last year at our tipi events, we had between 50 and 100 people attend. During our tipi events in 2018, we see between just 10 and 20 people – which is a significant decrease.”

“We do our best to try to keep people informed, to try to speak with different people and offer first-hand experiences, and hopefully tell more stories of success – people who lived through it and suffered and came out on the other side.”

- Nick Kuhl

Part two: Looking around

The entire city is aware of these changes, in part thanks to coverage by local media, including the Lethbridge Herald. From stories about abuse, addiction and prevention, to coverage of the opening of a Supervised Consumption Site and concerns about needle debris in the downtown core, Kuhl (Communication Arts – Print Journalism 2008) as editor knew the issue was essential to cover.

“As a newspaper, we have a responsibility to our community as a news source, especially one that has been around as long as we have, to report accurately and balanced and in detail,” he says. “We do our best to try to keep people informed, to try to speak with different people and offer first-hand experiences, and hopefully tell more stories of success – people who lived through it and suffered and came out on the other side.”

Kuhl, who lives downtown and walks to work, stopping at neighbourhood coffee shops and saying hello to familiar faces on the way, says the story was important enough to devote an eight-page special section to in July. The special section appeared the day city council voted to continue to support needle distribution efforts offered by ARCHES and other health-care providers. Kuhl concludes: “I don’t think we’ve covered anything quite like this.”

That sense of never having seen anything like this rings true for those working in the corrections field as well.

“Corrections is always changing,” says Hoiland (Criminal Justice 1993). “But in my 25 years, I’ve never seen a change this drastic in this short of a time that demanded our staff to adapt. But our staff has risen to the occasion and is probably working harder when it comes to security-related issues than ever before,” whether by keeping “the movement of contraband out of our centres” or “communicating with each other and supervisors and outside agencies” including police departments, ARCHES and health services.

And those in the health-care industry are experiencing some of the biggest challenges. “I don’t think one day goes by that we don’t have multiple clients accessing our services for drug-related concerns,” says emergency mental health nurse Ross.

“And it can get frustrating when the same people come in with the same issues,” says Madisyn Chambers (General Studies 2014, Practical Nursing 2017), who now works both at Chinook Regional Hospital and at the college’s nursing simulation laboratory. “But you have to remember that everyone’s story is different. You can’t go into it expecting every case to be the same. One person might be using because a tragic thing happened in their past. You can’t judge anyone at all.”

At the Supervised Consumption Site, nurses like Michelle McKenzie (NESA 2012) provide many ongoing services such as assessing and treating wounds, infection prevention and education, vital sign monitoring and ongoing support.

“This population has often been mistreated and therefore they often don’t seek out medical help,” says McKenzie, who also works on a casual basis as a lab tech in the college’s simulation lab for nursing students, for the Supervised Consumption Site and in Health Services at the college. “I believe the site provides a safe place for clients to come and build rapport with the staff, making it easier for them to seek the medical attention they need.”

“This population has often been mistreated and therefore they often don’t seek out medical help,” says McKenzie, who also works on a casual basis as a lab tech in the college’s simulation lab for nursing students, for the Supervised Consumption Site and in Health Services at the college. “I believe the site provides a safe place for clients to come and build rapport with the staff, making it easier for them to seek the medical attention they need.”

McKenzie adds that for her, it makes sense to stay casual in her role at the Supervised Consumption Site. “I am one who would take it home with me,” she says. “So to do a couple of shifts there, and then come and do a couple of shifts at the college – it allows you to hold on to the positives that you do see.”

“I wish people understood the power of addiction. I think many people don’t understand the powerful hold it has on an individual and that it is not as easy as deciding one day to quit. I have also learned that the vast majority of users are victims of trauma in one way or another.”

- Michelle McKenzie

Part three: Looking in-depth

One thread uniting these professionals from such varied backgrounds is that their experiences have provided them with a deeper insight into the crisis in general and addiction in particular. And they agree on a number of topics – including the simple fact that addiction is not a choice.

“I wish people knew and understood that addiction is a disease, and that those who are using opiates are still people,” says Cortni Herman (Healthcare Aide 2014), who worked as a medical office assistant at an opioid dependence therapy clinic and now is in the process of launching a non-profit youth association. “Addiction and substance abuse don’t define who a person is. People from all kinds of backgrounds and upbringings battle with addiction… the statement that addiction doesn’t discriminate is true, 1,000 times over.”

Ross, the emergency mental health care nurse, adds: “I wish people would stop to consider that any addiction, even one to opioids, is an illness. It’s just as bad as other diseases, and it is essentially a terminal illness. It breaks my heart when I hear people say ‘why can’t they just quit,’ ‘just let them all die’ or ‘all they need is some tough love.’ It’s not that easy. It is an illness deserving of care, just as much as any other. They are all people too – someone’s mother, sister, daughter, aunt and friend.”

Hoiland, the deputy director of the Lethbridge Corrections Centre, echoes Ross’s sentiments.

“Addiction is an illness,” he says. “When I’m talking to offenders, talking to people who have been battling addiction for 20 or more years, they say they’ve never come across anything like this. …You don’t know what led a person to the addiction. No one puts their hand up when they are a kid and says I want to be addicted. You have to respect that this is a powerful, powerful disease and the less judgment we pass, everyone wins.”

McKenzie, a nurse, agrees. “I wish people understood the power of addiction. I think many people don’t understand the powerful hold it has on an individual and that it is not as easy as deciding one day to quit. I have also learned that the vast majority of users are victims of trauma in one way or another.”

As a police officer, Woods says she wishes people knew that fentanyl and meth use affect more people in the community than the average person is aware of. And meth is more of a concern to frontline policing as users “exhibit violent behaviours and turn to theft to support their habit – which has led to a 300 per cent increase in property crime reports this past year.”

Finally, she says policing alone will not solve this crisis. Without health services and addiction support, the cycle will continue.

Marie Laenen (NESA 2007), a registered nurse who teaches at the college in the Centre for Health and Wellness, sees change coming through trauma-informed care, a neuroscience approach to how the brain works differently, and the need to treat patients differently to get different responses. “And we recognize that addiction can really happen to anyone – it’s not just people who come from low-income homes – it’s across the spectrum,” she says. “And the one common thing is an unmet need for meaningful connection. Because the opposite of addiction is connection.”

Part four: Looking ahead

Just as these professionals have learned similar lessons throughout their experience of working with people affected by addiction, so too are some of their possible solutions remarkably similar.

“No matter how many barriers, I think it is important to remember that together, we will overcome this,” says De Groot.

They value education.

“There is a big need to reform education,” says SPHERE instructor Laenen. “A lot of children aren’t having their basic needs met – like food and love. Not everyone is coming to school starting in the same place but they are expected to finish in the same place. If we invest in help now, it pays off in the future. It may take more money now, but it will pay off down the road and make a difference.”

Hoiland at the correctional centre adds: “In a perfect world, one of the things we could look at is starting education about the power of addictions at a younger age – and better communication among everyone.”

“I am hopeful that – just like with drinking and driving – we will learn,” says Woods. “Society is learning, Lethbridge is learning, so are we as police officers. I am hoping the preventative and educational pieces will catch up. I hope that, like with seat belts, the younger generation will be better educated and have more knowledge to stop it from happening.”

They see the need for more understanding.

“My number one wish is that people would hold a little bit of empathy for other people and what they may be going through,” says Harmoni Jones (NESA 2013), the college’s health promotion coordinator. “I also would like to see people recognize our own privilege in that we don’t need a substance to cope or to continue living. I would like people to see that providing the smallest ounce of support can make a world of difference for our community.”

Cohen (Child and Youth Care 2003), the supervisor at Wood’s Homes, agrees. “I would encourage people to show compassion and understanding. Learn about trauma-informed care to determine the best ways to help people who are struggling with addiction and trauma.”

They see the need for more resources.

“If money weren’t a concern, I would love to see a youth detox centre and maybe some different forms of youth treatment,” Cohen adds. “And more affordable housing and subsidies for young people so they can go to school and work part-time and help them get a leg up. Everyone has strengths. I think we’d make a lot more progress if we worked with the good everyone has in them, with the strengths we can pull from anyone.”

“Our systems create so many barriers for clients,” says De Groot, who works at ARCHES. “There are long wait lists to get into treatment, and currently there are no detox centres in the city of Lethbridge. If we had unlimited funding, I believe our city needs more permanent supportive housing, affordable housing, detox centres and a smoother transition between shelter use and housing-first programs. We also need more money for transportation so that there is a means to get to detox or treatment on a regular basis. It would be amazing to have a place where all of the social services were offered under one roof, to eliminate the need for people to go to numerous agencies, trying to navigate the system.”

McKenzie, the nurse who works at the college and at the Supervised Consumption Site, points to both education and resources.

“I believe ongoing education and public awareness is one of the biggest ways to help communities understand and respond to the crisis,” she says. “It’d be great to see more detox beds here in the community as well as treatment facilities. I also believe we need more support to help victims of trauma and abuse – and that would hopefully play a role in prevention.”

And they agree there are no simple solutions.

“When all is said and done, I don’t think there is one solution to this problem we are facing,” says Ross, the emergency mental health nurse. “We are headed in the right direction but there is still a lot to learn. This crisis is affecting everyone from all walks of life.”

Woods, with years of experience as a police officer, adds that “it’s a multi-tiered issue. There are socioeconomic imbalances. It absolutely consumes people.” They also fall between the cracks for help, as “they don’t belong in a mental institution and they don’t belong in a jail. Mental health struggles and addiction can go hand in hand. Someone might be depressed and so they self-medicate. It’s a big cycle – you can’t really just treat one thing.”

But working together is the only way to start working toward these solutions.

“No matter how many barriers, I think it is important to remember that together, we will overcome this,” says De Groot. “With passionate, like-minded, empathetic people working together, we can break down these barriers and make the system easily accessible. If we focus on spending our energy and time on solutions to the crisis rather than complaining about it, we can help those struggling on their healing journey, whatever that means to them, and make this one heck of a community to call home.”